The Only Black Man in Medina, North Dakota

Originally published in Entropy Magazine. Republished here upon closure of the journal.

The Day

When we pulled in the campground owner was waiting for us in a pick-up truck that had seen better days. We’d called early asking for firewood. Rolling down his window he said, “I’ve got your wood all setup at your spot already.” He was a stocky man with brown hair peeking out from beneath his dusty baseball cap, his tanned skin like well-worn leather. When he smiled, wrinkles surfaced around his eyes. He had a carpenter’s hands, bulbous from years of abuse. I want to say that his truck was red with a wide white stripe racing around the sides, but that could simply be me projecting my idea of what it should look like to properly personify this place. He looked surprised to see us when we rolled down our windows, or maybe just me, the only black guy in the group. It made me wonder if I was the first black man he’d seen in the flesh in the last decade.

A few days into our trip we found ourselves in Medina, North Dakota, a small town of just over 305 people. When we drove into its small campground that number rose to 309. In 2015, Medina had a zero percent African American population; I almost certainly was the only black guy when we pulled up. There was something magical and eerie about such a small, quaint place like Medina, at least to a city boy like me. I was used to the streetlights and city skylines of New York, Detroit, San Francisco, even the small city I was from, Grand Rapids. The steady flow of cars whizzing through crowded streets, the anonymity of walking past people I’d never know, their stories only as elusive as my imagination allowed them to be. Medina was the kind of small town, I imagined, where no footstep went unnoticed, no story was left unread, no children were unaccounted, and the store owners knew everyone’s names and orders by heart. The kind of small town where skipping school meant walking across the street to your parent’s house because there wasn’t anywhere else to go.

A large water tower lumbered over the stout town buildings down the road from the campground. Painted onto the sky-blue tower was, “Medina,” with a pelican—wings outstretched—flying over it. An empty baseball field rested adjacent to the camp parking lot with a large, black, chain-link fence that reminded me of the ones I’d used to try and climb with friends in middle school. The grass was a vibrant green, standing as straight as a washboard, uniform and uncompromising.

I would like to think that it was our car that surprised him, it wasn’t exactly inconspicuous, a large decal of our logo—a loon that looks maybe a bit too similar to the Penguin Books logo—wrapped around the body.

“What brings you all out here anyway,” he asked, getting out of the pick-up.

“We’re on the road doing a podcast,” Ben replied, pulling the car into our parking spot.

“Like he knows what a podcast even is,” I say beneath my breath. In the backseat, Shira and I try to contain our laughter.

“A pod-cast, aye?” the man replied.

“It’s about death, belief . . . And the supernatural!” Evan barked in a horrible southern accent. Ben grumbled.

“It’s like . . . a radio show.” Ben said opening his car door.

Getting out of the car we followed the man to our campsite. After a few moments of small talk, he said, “If you need something to say about Medina in your pod-cast, the most interesting thing to happen in Medina since electricity,” his eyes lit up, a subtle smile revealing his yellowed teeth, “is a fatal shootout between a crazy guy and some law enforcement officials twenty years ago!”

*

After I graduated from college in 2015, Evan, Shira, Ben, and I started our podcast called The LoonCast, and ventured out on a cross-country road trip to get stories for the show. In our eyes, it was a project that was entrenched in conversations revolving around death, belief, and supernatural topics (although we would later change this to “metaphysical topics” after so many people thought we were ghost hunters). We traveled over 8000 miles during the summer of 2015 interviewing a variety of people: “Elkhorn John,” a lanky, old surfer with a bloated gut living in a ghost town in the mountains of Montana; a Louisiana couple who had switched apartments after seeing demons scurrying across their walls at night; two women convening with their dead dog through a psychic over the phone; the docent of Colma, California, a purposefully built Necropolis thirty minutes out from San Francisco. But Medina has stuck with me the most.

*

“Well, if somethin’ comes up, you all have my number,” he got back into his pickup truck, and drove off leaving a thick cloud of dust lingering in the windless air. The grounds were nothing special: a small bathhouse was on the other side of the park. Next to it, a jungle gym with a slide and monkey bars that looked as if it they hadn’t been touched in ages. Peppered throughout the field were benches with flaking paint, fire-pits filled with ash from previous campers, and hybrid poplar trees. We weren’t the only ones staying here, two tour bus-sized RVs were parked on the far end of the grounds near the bathhouse, and a precarious mobile home—the kind you’d drag behind your truck—sat in a parking space a few spots from our car, unattached to a haul. We quickly began unloading our car—tents, cooking utensils, clothes, cleaning supplies, baseball mitts—and slowly made the small plot our own. Ben and I were sharing a ten, it was an obnoxious lime green color. Clumsily we affixed the metal rods that kept the tent standing, they were beaten and bent from years of ware, and used a hammer to drive the stakes—a mishmash of pairs from various camping sets his parents owned—into the ground. I didn’t know of any black people in my life that enjoyed camping or the outdoors in the sense of wanting to “rough it” in the woods. I had watched enough movies like Into the Wild, National Lampoon’s Vacation, and just about every teen horror movie that involved camping to know that road trips, the kind where you stop in the middle of the night and campout, was a strictly white thing to do—even if your black friend tagged along.

Evan eyed the baseball field across the way, “So, who’s down for some catch?”

“You know I am!” Ben said, catching the mitt Evan tossed his way. “You in, Phil?”

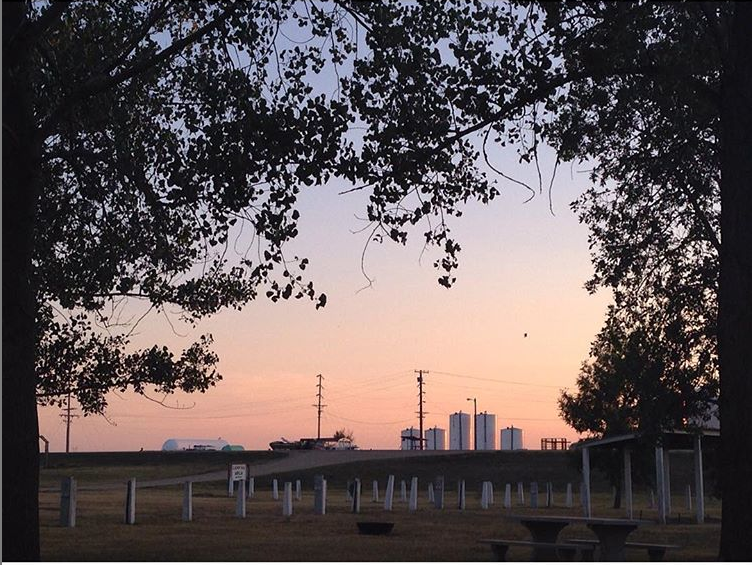

“Sure,” I said. I had no interest in baseball or camping or Medina, North Dakota, but there I was, trying them all out. The land was so flat that it felt as if the baseball field stretched for an eternity. I felt small. Forgettable. Across the street from us was a tiny cemetery, a rusted metal gate maybe four feet tall, closing it off from the world. My arm strained as I tried to throw the ball across the field to Evan. Shira crouched low to the ground, her wispy brown hair falling over her face, as she took a picture of Evan mid-throw. The thud of the ball hitting my glove on the return felt satisfying. The sky, pale blue, the emptiest I’d ever seen it, quickly washed into a light pink hue as we walked back to our camp.

The Dinner

We prepared dinner as light began to slip away. It was a feast, something I wasn’t expecting when I thought of a meal by the campfire. Salad with homemade dressing, fresh tomatoes and cucumbers, baked beans, hot dogs cooked on the fire. Cooking always feels right in the open air; the sizzle of meat on a pan, the crackle of wood ignited—it’s primal. The heat of the flames burning my legs. A good hurt.

After we’d finished eating, we sat in silence and listened to Evan play his guitar. It was an eerie song that seemed to fit perfectly with what I imagined a campfire tune to be. I watched his hand glide across the frets, his strumming fingers were slender and pale with long nails jetting out from his thumb and index finger. His voice had a ghostly quality to it, quiet and airy, uncharacteristically high-pitched. “Play it again” I urged him. He smiled and started from the top. Ben left Shira, Evan, and me at the fire to go work out—he always took some time to decompress before bed.

That’s when it all began.

As we sat chatting, a truck pulled in to the parking lot stopping behind our car, boxing it in. Two men got out of the idling pick-up, their boots scratching against the dirt road. The petering muffler of the truck grumbled into the night as they entered the vacant mobile home. “That’s strange,” I said. “Why’d they box us in?” Shira added. We packed the cooking supplies and brought them over to our makeshift sink, as I scrubbed at a gritty pot, I thought about what those men could be doing in that trailer. Maybe they live there? They own it and just forgot something, a quick trip. That’s why they boxed us in—it’ll only be for a minute. After a while, the men exited the mobile home, moving silently through the darkness toward their truck, it’s idling engine growling like a guard dog. They stood in front of their yellow headlights for a long while—or at least it felt that way—talking about who knows what. Despite the silence near our camp, I couldn’t make out a word of what they were saying. Their white skin glowed in the car light, casting elongated shadows across the unpaved road. They looked like how I expected rural white folks to look: flannel and blue jeans, beaten-up brown work boots, baseball caps adorning their greasy, roughly cropped hair. My heart, like an unanswered fist, knocked against my chest. Evan went back to the car to put away his guitar, and I watched, waiting for the two men—feet away—to grab him and drive off into the night.

*

For most of my life I’ve strayed away from viewing negative experiences I’ve had through my race. I know this is foolish, but when it’s happening to me, hell, even when what’s happening to me isn’t what I think is happening, it’s hard to quell that feeling. I’ve never wanted to accept these moments occurring because of the way I looked, despite history’s persistence to beat me over the head with that very truth. Moments like these were reserved for when my parents were young, that wouldn’t happen to me, Phillip Russell, the upper-middle class black guy who somehow crowd-funded thousands of dollars to travel around the country with three of his friends to create a podcast. There is a shame associated with the acknowledgement that sometimes, our fears are intrinsic to our experience, especially if you are black living in America. They are like brands given to us at birth and sometimes those anxieties are inescapable, we didn’t ask for them or see them coming, they just were there, they just are there.

*

“They didn’t even acknowledge me,” Evan said when he returned. “We even made eye contact.”

“It’s probably nothing,” I said, though I didn’t believe it.

Shira peered into the dying flames of our fire as Evan blew air into its center. “Ben’s been going a long time, don’t you think?” She asked in that way that’s not really a question, but a call to action.

“It feels that way, at least,” I said, trying to keep the conversation going—keep our minds off what we thought the men might do. At that moment, I wanted so badly to say, let’s find Ben and get the fuck out of here. We’d spent eight hours driving, but another eight didn’t seem so bad if it meant that I’d still be alive to complain about it. The two men rummaged through their truck bed pulling out what looked to be an air conditioning unit and began installing it in the mobile home, the adjacent light from the inside of their truck the only illumination they had. Another pick-up showed up, took one quick, roaring loop, and sped off into the night.

The two men working on the mobile home didn’t seem remotely phased, it was as if this always happened in the middle of the night at this campground in Medina. I wanted to believe that this always happened here, but that was one lie that I couldn’t convince myself was true. Two or three more men shuffled out of the two RVs parked near the bathhouse, greeting each other. In the darkness, they were mere shadows of themselves, I could hear the murmur of their voices, their feet skirting across the grass, their doors slamming shut as they stalked around. They went in and out of the adjacent vehicles in a seemingly endless procession. Eventually, they wound up next to the men working on the mobile home in the dark. They knew each other, it seemed. I don’t think they’re campers . . . I think they live here, I remember thinking to myself. They all lived here, and they wanted us gone. In fact, they were plotting on how to get us to leave, even if that meant killing us or at the very least, me, I was sure of it.

The Dark

They say that North Dakota is so flat that you can watch someone run away for days. It wasn’t until later, when the darkness had completely enveloped us, that I wondered if that someone would be me.

*

My mother is a small woman with an ever-changing hairdo, her freshly done nails often bookending a cigarette in hand. She’s fair skinned for a black woman, so most people think she’s white, and I’m mixed. What she lacks in height she makes up for in personality; growing up in New York taught her to be hard, to not take shit from anyone. Despite all of that, she has always been an anxious person: she worries about everything from what to wear, what to cook, how dirty the house is before the cleaning lady shows up, what the weather will be a week out, where the exits are. The rest of my family used to joke that The Worst-Case Scenario board game was based off her thoughts. If you swam in the ocean, you most certainly would be eaten by a shark; if you walked home alone at night, you were going to get mugged. Plan for the worst, it’s bound to happen. Her worry used to drive us all crazy.

My parents have something in common, though: they’re constantly worrying about where the exits are located, the most efficient places to sit in a crowded room or airplane to reach the bathroom or duck out quietly. My father refuses to sit in anything but aisle seats in the movie theater. Is this anxiety learned through experience? Or is it planted in us, waiting to break out of its shell and blossom? They were both born before the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Both have told me stories of their respective family road trips: driving through the night to avoid staying in small towns like Medina all throughout the Midwestern and Southern regions of the United States.

For a kid growing up in Grand Rapids, Michigan, with a big house in the suburbs, money, a private education in the city, and a friend group of mostly white kids, listening to my parent’s tales might as well have been the same as listening to scary stories by the campfire—they were scary only as long as the fire was burning. I couldn’t relate. My fears were simpler. Until I was in fourth grade, my parents often woke in the morning to find me, pillow and all, on the ground asleep by their bed. Sometimes they would notice me in the middle of the night curled up in the white blanket I’d had since birth, and tell me to go back to my own room. Recently, when I brought this up to my mother she had little recollection of this happening at all, but I know it did, and it went on for a long time. When I questioned her further, “why did I do that? Was I afraid of the dark or something?” She simply replied, “Yeah, that must have been it,” before telling me about whatever show she was obsessed with at that moment.

I do not doubt that was the case. Don’t we all have that fear growing up?

But as I got older, my fear of the dark morphed. Just as my parents obsessed about exits, I, too, began noticing them. When it was time for bed, I would stay up at night debating whether to keep the door closed or open, convinced that one day a burglar would break into our house and I would have to be ready to run, hide, or fight. The question of where the exits were located became harder to grapple with when the only feasible escape route in my room was also the only entrance. If the door is open and I’m awake, I could see them coming! I would tell myself. Yeah, but what if you aren’t awake? Then you’re toast! If you have the door closed, you’ll get woken up by them opening it and can react! These circular arguments consumed me until I eventually would pass out from exhaustion or conclude, Well if I’m going to die, so be it.

I realized, sometimes there are no exits to escape through, at least not physically; sometimes we are imprisoned by our own bodies. Sometimes the only respite to be had is to turn off your brain and let whatever is going to happen, happen.

*

The campground in Medina presented its own exits. The land stretched out, unobscured, for miles in every direction—a sea of grass and corn. Everywhere was an exit, an entrance, an escape. Where was I supposed to hide when the men skulking in the shadows a few yards away finally made their move? I ran through scenarios in my head, one went like this: take off running west, through the corn fields, their long blisteringly yellow stalks beating against my face, obscuring me from my pursuer’s view. I pictured headlights cutting through the darkness, illuminating my back; dagger sharp pain in my lungs, my muscles constricting as I stomped over unevenly tilled ground.

I wouldn’t be able to out run a truck, I decided. I settled on something simpler, the only exit was to get in my tent, cradle the large, blue, Swiss Army knife my best friend’s father gave me before we left for the trip, and be ready to fight for my life.

The Decision

Ben returned to our campsite long after I’d decided my fate. Nestled in my extra-large sleeping bag, knife practically assimilated to my palm, we lay in silence. It was hot and sweaty in that tent, North Dakota wasn’t exactly cold in early August, and my body’s radiating heat, tried it’s best to bust through my sleeping bag. If it had, we may have even taken off like a hot air balloon and drifted away from Medina to some place civilized like Minneapolis, where we’d just came from. After a while, I broke the silence, telling him everything that had happened during his absence, comparing his story with mine, trying to assemble the puzzle with any pieces I may have missed. “You don’t want to be a black guy in a town like this,” I told him, a mix of fear and jest coloring my voice. Ben didn’t experience a lot of what Shira, Evan, and I had, but a few things lined up, notably, the pick-up truck that had barreled through the parking lot like a bat out of hell. Ben could tell I was afraid, “we don’t have to stay here if you don’t feel comfortable,” he said, shifting in his sleeping bag before continuing, “we can go. I don’t mind driving at night.”

“No, we can stay,” I replied, I didn’t want to give in to the fear, to admit that I was afraid. I didn’t want to say, I’m the only black guy here, that’s why I’m feeling this way, that’s why I’m afraid! We talked for a while longer, I probably was making jokes about the men outside, trying to take my mind off things, and eventually I fell asleep. I was okay with the fact that at some point in the night, a man would come over, slice our tent up, and gut me, maybe even Ben too, if he was feeling extra angry.

Ben and I woke early in the morning, long before Shira and Evan. Atop the green vinyl ceiling, water droplets accumulated, and slowly fell down the tent’s sides. I watched them for a while in silence, the swiss army knife that, only a few hours ago, was glued to my hand, had disappeared in the depths of my sleeping bag. The darkness that crippled me in the past was replaced by a white light. Unzipping the tent, we were surprised to find that fog had descended upon the grounds, misting the grass. The individual blades, once straight, were now bending under the weight of the water left behind. We decided to take a stroll through the town while Evan and Shira slept. The men and their truck had left, leaving the mobile home exactly where it was. The RVs still sat across the way, and to my surprise, the cooking utensils, food, our carrying crates, even the bougie organic dish soap Shira brought from home were all still there.

“Let’s go check out the town,” I said to Ben after he returned from brushing his teeth, he nodded in reply.

We walked along the roadside up to a small building. Outside of it was an informational plaque, the kind that tells you about all the local animals and trees in the area. I wondered how many people who weren’t from Medina actually had looked at them. Walking into the town put into perspective just how small this place was. The first building we came across was “Coffee cup café,” it’s small doorway didn’t perplex me as much as the Dr. Pepper sign above the logo did. Next to it seemed to be the only bar in town, crudely painted brown and tan camo adorning the buildings’ front side. After that, a small bakery, then a diner, and a general store. Nothing stood out. I stared at my reflection in one of the storefront windows as we passed by, my hair matted against my scalp from the weight of sleep, my light brown skin illuminated in the sunlight. The town was empty. It was as if overnight the 305 people who resided in Medina had packed up their things, and driven into the night, away from this place. After only a few minutes of looking—that was all there was to see—we started back toward the campground, the gravel spread across the roadside crunching beneath our feet. Once we were back at camp, we packed quickly, filled up on gas and coffee at the local Cenex, and left without a hitch.

*

I spent days pouring over my memory trying to find reasons to explain why two men, thick flannel hugging their chests, were installing an air conditioner at night. I hoped that the campground owner was wrong, that there were other notable things to have happened in Medina, gruesome things even, death and violence fueled by racism to justify the fear that had imprinted itself in my mind that night. I searched Google trying to find some article about a black kid who had been killed in Medina, hell, even the town over, but nothing came up.

Whenever my mother suspected that I had been bad or had something on my mind as a child, she would me tell me, “the truth will set you free.” I always felt it to be such an easy thing for her to say, and an even easier thing for me to disregard, but if I acknowledged my fear that night, confronted it in some way, admitted that I was scared as hell, maybe things would have been different. Maybe I would feel different. I wouldn’t be pouring over pages, writing through the anxieties I’ve tried so hard to bury deep inside. I might have realized earlier that it’s okay to let the fear that was planted within my heart so long ago burst free, bellowing for the world to hear.

Post a comment